An already struggling industry has found itself thrust into the spotlight, weaknesses previously observed now under further scrutiny, with cracks not just forming but separating and breaking into pieces of what is the beginning of much (needed?) destruction.

Dramatic enough? Take a deep breath. Pause. Think. These actions seem to be the only things I can take comfort in while finding myself and the rest of the world desperately trying to swim out of the maelstrom created by the now infamous COVID-19. Among the many ships that are currently sinking, I’m a fellow passenger on the Oil and Gas cruise line, more specifically, the Shale Shitshow Line which may soon become The Ghost Ship at least according to some (nod to those who know which movie I’m talking about). Yes, while the shale industry hasn’t been able to escape the microscope of skepticism and scrutiny the past few years, it has now had thrust upon it an even larger lense. It’s not that more weaknesses have been discovered, only that the prevailing weaknesses so long submerged are now being exposed to a much larger group. The future of the shale companies (or shitcos as some like to refer to them) has been called into question and is rife with speculation. I’ve been along for the ride since the early 2010’s and embarrassingly and admittedly feel like I woke up today and started asking myself questions I should have been asking myself years ago. What happened? How was an industry able to convince so many of its promising, bright future? How was it able to continue for so long? What exactly did it fail to deliver? Some of these questions many may know the answer to. I certainly feel that I do, but as a skeptical, optimistic, ignorant engineer, I wanted to investigate for myself and explain to me why I’ve been doing what I did for the last decade. In addition, I’ve focused on the oil shale players (as opposed to the gas guys), so forgive me if you we were wanting to hear more about them.

First, a little bit of history

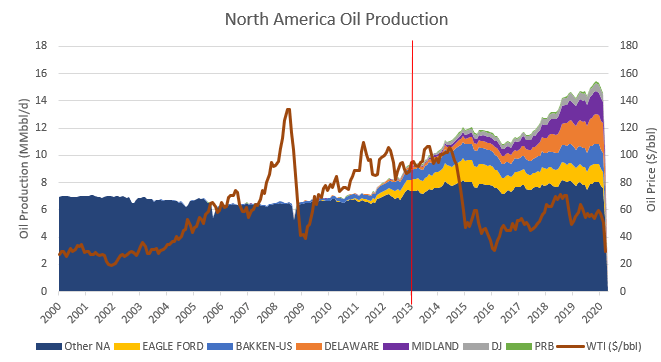

Let’s remember where we were before the shale revolution. US oil production had been in decline since 1985 when prices tumbled from ~$30/bbl to the low $10’s. Beginning around 1993, oil imports started to exceed US oil production to meet the growing US oil demand. By 2008, oil imports were nearly double US oil production, highlighting our ever-growing dependence on foreign sources to feed our energy-hungry nation. Predictions of peak oil started to surface, notably highlighted in Matthew Simmon’s “Twilight in the Desert”, which concluded that Saudi Arabia’s spare production capacity was overstated and that the world would soon be in an oil crisis. We were going to run out.

Just around the same time, the Bakken in North Dakota was beginning to get more and more attention as operators started to drill horizontal wells in the Middle Bakken formation, part of a source rock system with billions of barrels in it. The initial results were abysmal but operators began to improve, switching from open-hole and slotted liner completions which gave no control over where the operators were pumping their completions to isolating the wellbore into “stages” using swell packers, giving the ability to pump targeted completions over a smaller area one stage at a time. Early movers included Hess and ConocoPhillips through their legacy positions and Continental and EOG who took a more organic leasing approach. In 2010 on the opposite side of the country, EOG very quietly discovered the Eagleford in South Texas (as opposed to Petrohawk’s big announcement that spurred a leasing frenzy) with a specific intent to target oil producing shale. Recall that up to this point, shale wasn’t new but it was primarily thought to be a gas producing play concept (the Barnett in Texas). The discoveries of the oil producing Eagleford and Bakken helped spark what would eventually become known as the “shale revolution”. A rediscovery of oil in America’s backyard. A solution to the future of America’s energy security. A period of time where much money was spent, much production was produced, and much capital was not returned (for shale and non-shale alike).

Fast forward to 2013. This is a year in which the Eagleford and Bakken are the two hottest shale plays and the Permian (made up of the Delaware Basin, Midland Basin, and Central Basin Platform) is starting to emerge as the slobbering, mumbling, big-headed beast that it is today. WTI is hovering between $90 – $100+. I’ve secured my position as a reservoir engineer for a big Bakken operator and I’m crushing it with pre-drill packages promising single well IRRs of 100%+ on the company price deck. What’s it look like using the NYMEX forward curve? Even better. Get. Me. That. Oil. Now. You. Engineer. You.

With oil dipping into and near triple digits, we could justify doing pretty much anything we wanted to back in 2013. Drilling tier 2/3 acreage still yielded returns based on our optimistic outlooks and allowed us to get a preview of what to expect further down the line when we ran out of all the good stuff (i.e. where we are currently), but the focus was still in what we considered our core areas. We were shifting from drilling wells to hold acreage (drilling a single well in a unit) to drilling the rest of the wells we thought we could fit in the unit (drilling infills), shifting into full-field development mode.. FACTORY MODE as some like to say. The goal was to grow production (and ideally value because production = value right? not really) and while in hindsight we made a lot of mistakes, I can still say proudly we weren’t as shitty as Hess. Life was good.

Understanding the narrative

While I remember what my bubble was like, I wanted to go back and look at some other key operators at the time to see what they were saying. How they were viewing the world and if their perspective was as muddled as ours or if there were some more reasonable minds prevailing. I selected a few players to look into specifically: EOG, Pioneer, Continental, Oasis, and Whiting. You could argue that I should have selected others for my analysis, but I chose these operators because they were early entrants into the shale plays and didn’t have a lot of non-shale production beginning in 2010 (companies like Hess, Marathon, and Devon had larger international, downstream, and/or offshore positions earlier on, making splitting out their shale performance in the earlier years more difficult.)

So rather than rely on my anecdotal examples, let’s see what shale companies were talking about back in 2013. What were executives actually saying? What were analysts asking them about? Does anyone actually pay attention to analysts? To answer these questions, I started diving into earnings transcripts (thank you SeekingAlpha). Unfortunately, I was unable access presentations prior to 2015 as the company’s websites didn’t archive them and SeekingAlpha didn’t go back any further (if anyone knows of another way, please let me know). But what there’s great record of are the earnings call transcripts, which give a great glimpse into what the focus was in each period, what were people worried about (nothing) and excited about (everything) when it came to shale? Below are some direct quotes spanning a variety of topics:

An American energy revolution

“Since our initial public offering in May 2007, we’ve created outstanding value. In the process, we’ve participated in a historic energy renaissance in the United States that is literally changing our entire world. This renaissance will have a profound positive impact on U.S. Energy Security and our economy. Continental is increasingly and rightfully recognized as one of the key leaders in American energy renaissance given our leadership in these strategic plays” Harold Hamm, 4Q13 CLR earnings call

Growth, growth, growth

“Continental remains a high-growth company committed to exceptional production growth. Last year, we increased production, 39%, almost entirely through the drill bit and we’re on track to achieve our 5-year goal of tripling production by year end 2017. That means by year end 2017, production should be roughly doubled what it is today. We’re focused on strong profitable growth.” Harold Hamm, 4Q13 CLR earnings call

“While I discuss 2014 business plan in greater detail later on in this call, EOG is targeting 27% oil production growth in 2014. Given the strength of our balance sheet and the depth of our high margin domestic crude oil drilling inventory, we have increased CapEx levels over 2013 to accelerate drilling of the high rate return oil inventory. Last year, we added two new locations for every one well we drilled. With this strong operational momentum in our key areas of activity, we plan to keep it going.” Bill Thomas, 4Q13 EOG earnings call

“We’re targeting 16% to 21% compounded annual growth rate from continuing operations from the ‘14 to ‘16 period and we easily expect to more than double production by 2018 compared to 2013. We have a great set of hedges in place for 2014 protecting at $93 on the downside with upside to $114.” Scott Sheffield, 4Q13 PXD earnings call

” …we were able to grow our annual production by 51% in 2013 to 33,900 BOEs per day with fourth quarter production of 42,100 BOEs per day. Our estimated net total proved reserve grew by 59% to 227.9 million barrels, while the PV-10 of our estimated net proved reserves has grown by 69%, up to $5.5 billion.” Thomas Nusz, 4Q13 OAS earnings call

EURs increasing, downspacing wells, and new horizons (remember the lower three forks?)

“In 2013, we repeated this by exploring with productivity and density test to lower benches in the Three Forks…As our Hawkinson density test demonstrates, the Three Forks package is larger than anyone knew just 2 years ago. And it should be a significant contributor to our production in proved reserves growth in the years ahead.” Harold Hamm CLR 4Q13 earnings call

“[on Eagleford] I think we have done some in the 300-foot range and that’s 200-foot maybe down to 200 feet. Again, we push them pretty close together and the goal of course is to always to maximize the NPV of the acreage. As you push them too close together, you could start destroying the value, so these pilot programs that we put in and tested have given us a pretty solid understanding of the interference between wells and the spacing between wells in terms distance between wells, so we feel pretty solid at this point that on an average 40 acres is probably the optimal spacing pattern” Bill Thomas EOG 4Q13 earnings call

“[on Redtail asset] In the second quarter of 2014, we plan to begin drilling a 960-acre spacing unit on a 32-well pattern. If successful, our potential drilling locations would increase to more than 6,600 gross wells. Our 30F pad located in our Horsetail area will test the Niobrara A, B and C zone…We estimate the total resource potential for Redtail to be 492 million BOE net to Whiting. This is why we believe Redtail is another current Whiting.” James Brown WLL 4Q13 earnings call

“We feel like Midland County is our best sweet spot for Wolfcamp B. We feel very good about going to a 1 million barrels of oil equivalent, 100% type returns. The Wolfcamp A in Midland County remember we only have one well now we have several wells scheduled for ’14. In addition to the Wolfcamp B in Martin County we’re assigning 800,000 barrels of oil equivalent over a 100% plus returns and the Wolfcamp D both in Midland and Martin and Andrews County, 650,000 to 800,000 barrels of oil equivalent, it returns between 45% to 95%.” Scott Sheffield PXD 4Q13 earnings call

“…we expanded our inventory with tighter down-spacing and additional lower bench Three Forks wells. We now have 3,590 gross operated drilling locations, up 78% year-over-year, which provides us approximately 17 years of drilling inventory with our current rig plan.” Thomas Nusz OAS 4Q13 earnings call

” we will drill approximately 10 wells per DSU.” Thomas Nusz OAS 4Q13 earnings call

Believe it or not, there was some focus on costs

“Our 5-year goal was to reduce well costs by an average of 3% to 5% per year, and again, we did A plus work in the first year. Our 2013 goal was to reduce Bakken well costs from $9.2 million to $8.2 million by year end or 11%. We made so much progress in the first half, we lowered the goal to $8 million and we hit that target in the third quarter. So the first year, we have a 13% reduction in well costs.” Harold Hamm CLR 4Q13 earnings call

“…we will continue our focus on reducing well cost even further, while enhancing the productivity and recovery factor of the field.” Billy Helms, EOG 4Q13 earnings call

“First, we were able to complete 136 gross operated wells, which was 8 more than we had budgeted, and we estimate we will spend approximately $40 million less in drilling and completion capital. We’re continuing to get more efficient as we’ve driven our well cost down from $8.5 million in the fourth quarter of 2012 to $7.5 million as we exited this last year” Thomas Nusz OAS 4Q13 earnings call

But there is no mention of free cash flow by companies or analysts. A quote below from Whiting is indicative of the sentiment around profits

“Right, and I didn’t want — I did not want to leave you with the impression that we’re saying the dollar volume of our capital budget is going to remain flat. It should grow with production. My point was that as we grow, we’ll try to keep the amount of capital that we invest and our discretionary cash flow equal or pretty close to one another, so that we’re not outspending while we grow. James J. Volker WLL 4Q13 earnings call

And one lucky/prescient call from OAS, the only mention of potential for lower prices

“But keep in mind that, too, is based on current well cost. So — and then as we go down, if we do, to call it $50 to $60, we still got a good bit of inventory — a lot of inventory, actually, that’s economic, very economic down in that price range. So that we can continue to drill with, call it, 6 or 7 rigs, in that low price environment.” Thomas Nusz OAS 4Q13 earnings call

Remember the Lower Three Forks? Whiting’s Redtail field which was supposed to be “another Whiting?” A lot of quotes to shuffle through here, but the main theme is how fast can we grow? Throughout the earnings transcripts, production and reserve growth are one of the first things management teams brought focus to as an accomplishment for the year. Analysts wanted to know what the next few years of production look like, how close can you space your wells, how deep is your inventory, how much improvement are you seeing in well performance, how many rigs will you run? All of these things have implications on the ability to grow. There is no reference to the ability for the corporation to generate free cash flow, to self fund capital programs, to have a path to a sustainable business. Why so much focus on growth?

“We also currently believe we have access to the public equity and debt markets, and we intend to maintain a balanced capital structure by prudently raising proceeds from future offerings as additional capital needs arise.” This is a quote from Oasis’s 2014 10k and is a principle stated under one of their business strategies. It’s also a stark reminder of what fueled the shale revolution. Another way of reading this quote is “we have no intention to self-fund our capital programs and instead will rely on the easy-to-access capital markets to maintain our ever-growing production ambitions.” The only company with any mention of goals to achieve free cash flow in their 2014 10Ks is EOG (who actually was free cash flow neutral in 2014.) So basically it really became about why not grow? The capital was going to be there and given the rosy outlook on oil prices, the asset value was more than enough to cover any liabilities these companies were taking on. It’s not that I believe debt is bad – debt is necessary to keep an economy booming and giving opportunity to those starting with nothing to really make a difference. But when your access to that debt seems like a fountain that will never sputter or shut off, your priorities begin to shift and the urgency to generate profits begins to be pushed out just beyond the horizon you’ve set your eyes on. The profits will be that much bigger X years from now if I just invest Y more dollars over the next Z years. You get greedy. We got greedy.

Building on some of the comments I made earlier about how I started my shale career, I’d like to divulge a little bit more about our processes. I say our as in our company – it’s not to say this is exactly how everyone else did it, but based on conversations with my colleagues and friends in the industry, quotes from executives and earnings presentations, the thinking was similar across the board. To justify our investments (whether or not we’d drill a well), we’d run economics on a pad of wells, estimating the capital and operating cost required to bring the wells on and maintain production and of course, estimate how much oil and gas we think they’d produce. The single well economics were the metric (mostly internal rate of return – IRR and Net Present Value – NPV), the ultimate hurdle to making a decision of whether to drill the well or not. If they passed the test, we’d add them to the drilling schedule and continue on down the line. And in theory, it made sense. The wells you drill are the source of the production that yields the cash flow to allow your business to run. They are the building blocks of your company. If the wells you’re going to drill aren’t economic, then you have no hope of ever growing your source of income. Your production will decline and you’ll eventually have no business. Using those single well economics, we’d build out our entire field development using the single well profiles for cost and production based on how many drilling rigs we assumed we’d run, how much production that would yield, and ultimately calculate the NPV of our asset. NPV and IRR don’t always equate to free cash flow. As some of you may know, to maximize NPV, you need to accelerate your cash flows to reduce the discounting effect on your future production volumes. In the oil and gas business, that means grow production fast, which means more rigs, which means lots and lots of capital.

And that’s exactly what we did. That’s what everyone did. We’d plug in our perpetual $100 price decks and stare in awe at the value we’d just created. It was a renaissance fueled by insanely high modeled IRR wells and an enthusiasm to match. By drilling high rate of return wells our business would eventually (keyword eventually) be flush with cash, returning capital back to shareholders and everyone could have a nice circle jerk. But that enthusiasm and ambition relied on two very important things – 1) a continuation of high oil prices and 2) a continuation of cheap capital to ensure we could keep funding our capital-intensive assets (remember, we weren’t generating in free cash flow ourselves).

The economics of shale

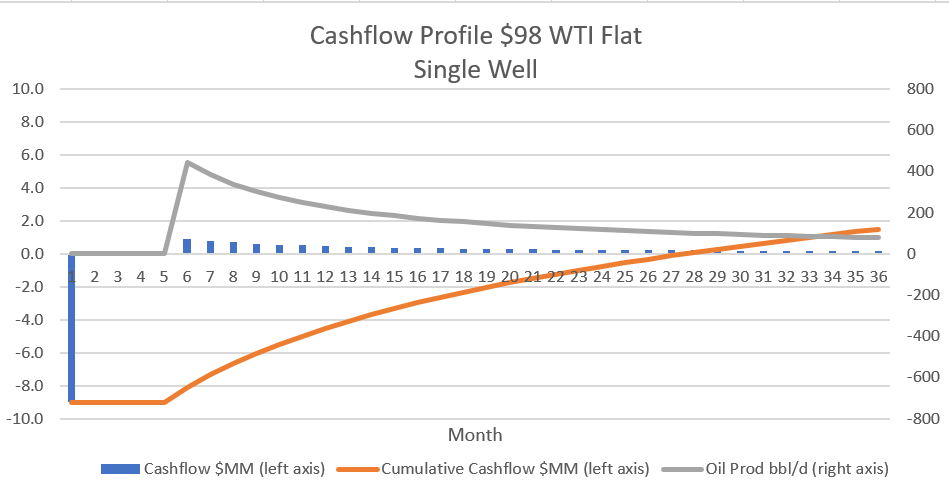

To better understand the economics of shale, let’s go through a few examples. To illustrate, let’s take an average Bakken well from 2013 (I’ve excluded Montana and Western Williams/McKenzie wells to try and capture the better part of the Bakken). I choose 2013 because that’s just before the wheels came off and when we were near or at peak shale ecstasy. This is a very simplistic model but I think it helps illustrate a few points.

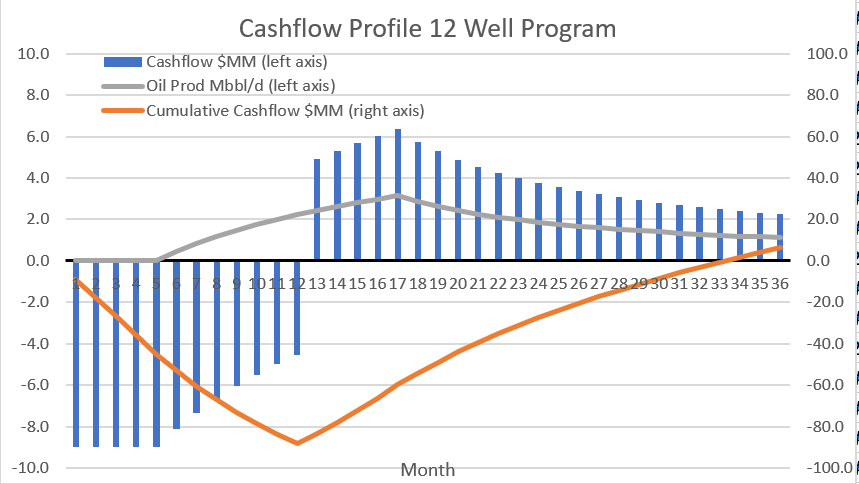

First, let’s examine a single well economic profile. After our big capital investment in month one of drilling, completing, and installing production facilities (in reality these should be spread out, but don’t get hung up on those details), the well comes online 6 months later and ends up paying out in about 2.5 years after my initial capital investment. Not bad. I’m free cash flow positive in month 6, but that’s just because I’ve stopped drilling. What does free cash flow look like with a continuous drilling program? Let’s take the same well as above and drill 12 of them back to back, one each month.

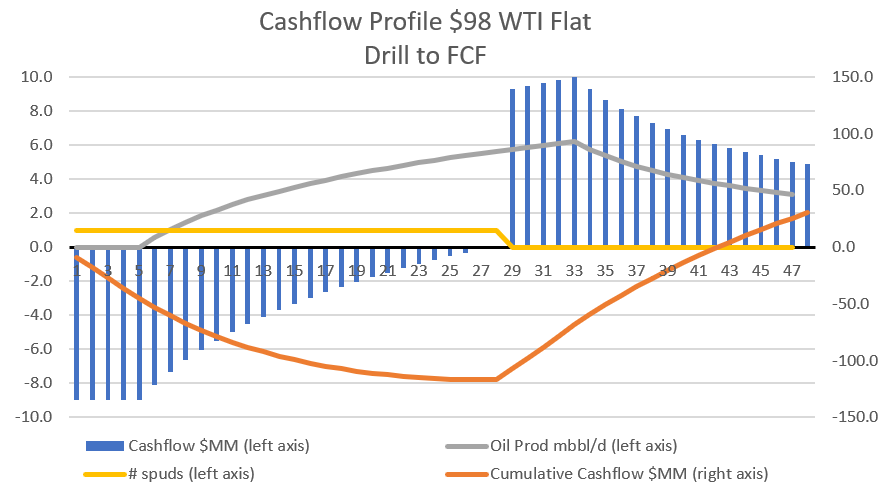

A few observations here. At the end of my drilling campaign in month 12, the negative free cash flow is reducing each month but I’m still not free cash flow positive. The production coming from my wells is still not enough to pay for the capital required to drill the rest of the wells in my campaign. I’m having to continue to pull from my pool of capital to keep my operations going. Also, the payout period for my drilling campaign has been pushed out another 6 months compared to the single well (the payout period being when the revenues generated from my production are equal to the amount of capital invested after paying my operating expenses). I’ve nudged that point of being able to see a return on my investment a little further out in time, leaving myself and my returns more at-risk to future changes in price. So how long do I need to go until I reach that free cash flow positive position? Let’s take the above model and keep drilling wells until that happens.

After drilling my 28th well, I’ve broken into free cash flow. The production from the previous 27 wells has built to a point where I can use that to pay for drilling my 28th well. As far as the pay out period of this drilling campaign, it’s now been pushed out to month 42 as I’ve added quite a few more wells compared to the 12 well campaign. A few things worth mentioning here – I haven’t assumed any improvement in operations, i.e. no reduction in well costs, spud to production times, or improvements in well performance which you could argue would pull the free cash flow and payout periods closer. However, I’m also not including cost of infrastructure, G&A, or interest expense from all the debt I’ve accumulated to fund this program. We need pipes to move the product, we need people to do the work, and we have to pay for the debt we’re using to drill. These are items that are often excluded from investor presentation economics but absolutely impact the bottom line.

Where am I going with all of this? The point is, significant investment is required to get to a point to where your operations are self-funding. Moreover, as you continue to develop your field, you push out the point at which your investment has paid itself back. I don’t know that this is a unique characteristic of the shale business, but what is unique is that the value of your future cash flows are primarily dependent on your commodity price which is absolutely out of your control and subject to volatile price swings (as we know all too well). Your pay out period is still a big question mark even when times are really, really good.

So what happens to development program when prices crash? Let’s take our 12 well program from earlier and extend it to 24 wells (i.e. two years). We can think of this as what happened to operators who started their 2013 drilling campaigns with lots of optimism only to see two years later oil prices plummet to sub $50 levels.

In month 25, oil prices crash to $50. We’ve reached the end of our drilling campaign and while we are free cash flow, it’s only because we’ve stopped drilling. The cumulative cash flow is what’s important here. At month 25, we’ve recovered ~50% of our investment but then the world turns upside down. Unlike the previous cases where we saw our cumulative cash flow cross into positive territory within a few years, it isn’t until 16 years out that it happens with this scenario – well off the chart. Our investment from the previous two years has been decimated. There’s no going back. We can’t drill ourselves out of shitty returns. Our oil price is now half of what it was, limiting the acreage you can drill (bye bye tier 2/3), but due to the rapid decline of my shale wells, if I just stop drilling for a while pretty soon my production will be a fraction of what it was.

So what does it all mean

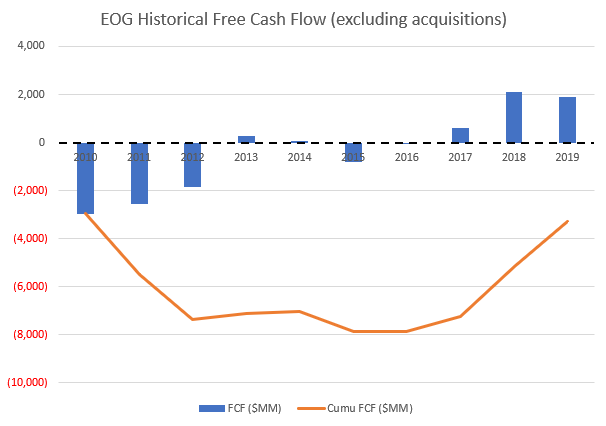

The industry was able to survive after the crash in late 2014 because the capital markets saw low oil prices as a buying opportunity. They still believed that shale could be resilient, they just needed to make it through to the other end, to when oil prices would go back up and these companies would emerge stronger than ever. Companies began cutting costs, tweaking completion designs and improving well performance at impressive scales year-over-year. Acquisitions only dipped briefly, sparking back up again in 2016/2017 making many of those in private equity lots and lots of money (we could spend a lot of time on this topic) and those acquirers piling on lots and lots of debt. But as time dragged on into 2018 and 2019, investors began to grow weary after observing the results of their second capital infusion into shale. Few companies were generating free cash flow, leading many to wonder “will these guys ever make money?” Focus began to shift from building deep drilling inventories and growing production towards the bottom-line. Prove to me you can make money. It’s amazing it has taken this long for sentiment to change to a more responsible tone. The amount of capital destroyed across the industry is striking. The industry darling in EOG has fared better the last few years, but even they have yet to recover all the capital they’ve invested over the last decade.

The recent downturn in prices driven by the COVID pandemic have shined the light back on the weaknesses of shale. The cracks have been there, it’s just that they’re more evident than ever before and are now exposed to a wiser world. There are of course a small minority who have been calling shale’s weaknesses out to the public and are only now garnering more popularity as some of their predictions proved prescient. What do I think? It’s complicated.

First, there’s a few fundamental things about shale that are critical to understand: 1) It costs a lot of money to take a well from a stick on a map to producing oil and gas 2) Once online, production declines rapidly 3) It is very empirical, meaning, we aren’t very good at predicting what we think will happen, so we often have to try drilling wells in different patterns with different completions first to see if it works (remember CXO’s Dominator pilot?) – if results are good, we’re still asking ourselves if we’ve waited long enough to feel confident in sanctioning a development plan 4) building on 3, due to the pace of shale development, an entire area of a field can be fully or nearly developed (in other words, a lot of $$$ spent) before you have a good understanding of the results 5) it is highly sensitive to oil prices (duh), but perhaps even more so because of 1 – 4 above. When your future is strapped to a commodity price you have no control over (well you can hedge but that in itself has its risks), you must remain ever more diligent to ensure survival.

The five fundamentals of shale are also its weaknesses. If I’ve learned anything in my career so far, there is no such thing as a “$50 WTI world” or $100 WTI world”. Any economics touted tied to either scenario are nothing but desires for a less volatile reality, which is far from what we live in. You have an industry held hostage by a commodity that itself is held hostage to geopolitics, social pressures, global economic activity, and many other things. How do you exploit that commodity and turn it into a business? The track record so far would say that if it sits inside a super tight rock, you can’t without continuous external support from capital markets. Yet, shale keeps surviving. Whether you agree with the survival tactics or not, one can’t deny shale’s utter resiliency.

But let’s recognize progress where it’s been made. Despite a lot of the negativity, there are a handful of companies who actually began generating free cash flow (outside of EOG there are PXD, CLR, and MRO to name a few) beginning in 2019, some earlier than that. No, it has not been enough to make up for the sins of the past and yes, oil prices are currently well below what they were in 2019, but it’s a damn good starting point. Will it continue? The challenges shale now faces outside of a low oil price are the political and environmental headwinds in addition to the deteriorating quality of acreage remaining. The latter will be the downfall of many companies over the next few years, assuming they aren’t bailed out with a sudden swing in prices (which is always a possibility). What I hope to see is a much-needed smaller group of companies with a lot less capital between them compared to years’ past, making the US less of an uncontrollable swing producer and one more focused on exploiting its resources in an efficient, cost-effective manner. It almost sounds like paradise.

For all shale’s criticism, one thing that isn’t cited enough are its geopolitical and economic implications. Recall the graphs from earlier showing how dependent the US (and the world) was on the Middle East to feed its growing appetite for oil. Without shale, what would the world have looked like over the last 10 years? Where would the incremental barrels come from to fuel the global economic growth, that would eventually drive oil prices down, lowering energy costs for consumers? How would the US’s foreign policy have changed without having the assurance of a large, domestic resource able to supplement its energy demands? It is easy to be critical of our past because it’s there – it actually happened and I can point to it and rehearse to you all the things we should have done differently. But it is those other “what ifs” that we fail to consider all too often.

Will shale once again emerge from another downturn? Yes. Do I think it will emerge more prudent and responsible? For the short term, I don’t think it has any choice but to. But what happens when oil prices spike again? Will there be another flood of capital to the industry, private and public, with all the lessons of history thrown out the window? We humans have short memories.

I still love this industry, enjoy being a part of it, and believe that changes are being made to allow it to survive. The world still needs oil and will for some time, although that itself is another topic for discussion. We survived 2008, 2014 and now face the Leviathan that is 2020. As somebody once said, third time’s a charm.

Obviously oil wells drilled with an $100 (or even $80) deck don’t work at $50. Also, so what that there’s commodity price risk. Capital itself is a commodity risk.

Check out biotech/pharma some time. Longer duration to cash flow. Bigger project costs. And higher uncertainty.

But capital itself is a commodity. Risk reward, risk reward. It’s all just basic MBA stuff.

The fact that oil wells decline and/or that there is commodity risk is public information. No secret. You can look at the EIA price “funnel graph” (calculated based on traded fixed price futures) and see that a year or two out oil prices are amazingly uncertain. Like $20-$100 for the 90% confidence interval. That’s just life. So what.

LikeLike

Congratulations on your MBA! Thanks for your thoughts and taking the time to read my post.

I think the point was to understand how shale companies went from being the darling of the market to being under the microscope as they were in 2020 (and still are today in 2022). 2020 vs 2014 were very different times, and even now 2022 is quite different from 2020 for a host of reasons. Prior to the run-up in price, companies were actually able to make the economics works at $50, showing that the industry was starting to make a turn for the better. Of course now, most companies are well in the money and so far seem to be exhibiting the same discipline they started showing in late 2019 before the pandemic.

It’s an exciting time for us – we’ll see how long that discipline hangs on. Perhaps we’ve finally turned the corner?

LikeLike